Climate-change policy encompasses policies formulated specifically to tackle climate change and can be local, national or international in scope. These broadly fall into two categories; those designed to minimise the extent of climate change – climate change mitigation – and those intended to minimise risks and seize upon new opportunities – climate change adaptation.

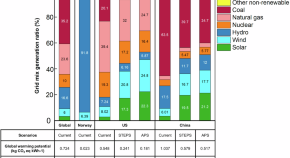

Electric light-duty vehicles reduce carbon dioxide emissions as the electricity grid mix becomes cleaner, but they may not mitigate particulate matter emissions due to electricity generation, according to life-cycle assessment and electricity generation forecasts in the United States, China, and Norway.

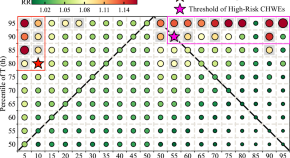

Over the past 40 years, human activities in China have led to high health-risk compound heat anomalies, especially in the Yangtze River region, which could be reduced by 2060, if carbon-neutral scenarios are implemented, according to analysis of the ambulance dispatch data, air temperature, and relative humidity.

Achieving the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement relies on every actor maximising their effort to reduce emissions. Generic targets claiming a basis in science have been used to justify inequitable efforts that insufficiently stretch the ambition of the best-resourced countries and companies.

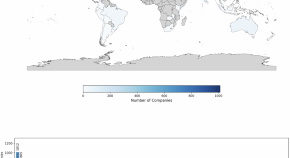

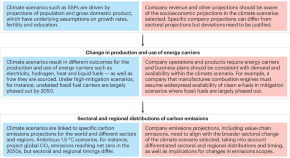

Currently, no comprehensive scientific methodology of corporate risk quantification, in response to new disclosure regulations, has been proposed in the literature. Here we develop fundamental principles that are important for the appropriate use of climate scenario science in transition risk assessments.

Loss and Damage benefits from the inclusion of Artificial Intelligence systems to support prevention and assessment. As AI research and development is highly dominated by western and private-led powers, the effectiveness of its use is limited for vulnerable countries. We call for an accessible, inclusive and locally-grounded AI to serve the needs of the most vulnerable, support Article 8 of the Paris Agreement and democratise innovation.

Governments are increasingly using industrial policy to develop low-carbon economic sectors and catalyse the energy transition. A recent study provides a framework to explain why governments adopt different types of green industrial policy, depending on industry position in the global supply chain and types of uncertainty.

Using carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS) for carbon removal is crucial to climate policy, but implementation at scale is at risk owing to political obstacles. Climate policies must avoid relying on empty promises of CCS for carbon removal without necessary financial resourcing and support emissions reductions separately from carbon removal.